Expanding Borders (1888–1895)

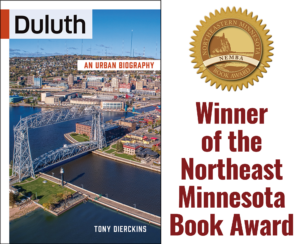

This perspective map of Duluth in 1893 was made by Henry Wellge. (Image: Zenith City Press)

The reborn city of Duluth hit the ground running, and its citizens kept Sutphin their mayor through 1890. The new city charter again called for a mayor-council system and doubled mayoral terms to two years. During Sutphin’s tenure Duluth improved its streets and sewers and built a city hall, police headquarters, and a new fire station. It also established a paid fire department, school board, library board, and Board of Park Commissioners led by William King Rogers, who envisioned a system of corridor parks along the city’s streams, connected by landscaped roadways following the modern lakeshore and the ancient shoreline along the hillside’s crest.

The city’s prosperity also caused problems. Typhoid epidemics in the 1880s led to the creation of St. Luke’s and St. Mary’s Hospitals. A strike by street and sewers workers led to a gun battle with police that left three dead and thirty more injured. In January 1889 the Grand Opera House—symbolic of Duluth’s success—burned to the ground. Nothing stopped immigrants and fortune seekers from flocking to Duluth, home to 33,000 people in 1890—but the Zenith City was running out of room to house them.

In 1891 Duluth annexed several “streetcar suburbs,” residential communities north and east of the city made attractive by their accessibility via streetcar lines, including Hunter’s Park, Woodland, Kenwood, and Piedmont Heights. Developers of Duluth Heights built a funicular railway, the Seventh Avenue West Incline, to convey its residents between their homes and downtown.

Duluth’s eastward expansion jumped from Endion to Fortieth Avenue East, the western border of Bellville, which in 1871 had been expanded and renamed New London. In 1886 the Lakeside Land Company purchased New London and property east to Seventy-Fifth Avenue East, creating the communities of Lakeside and Lester Park. Together they formed the Village of Lakeside, incorporated in 1891 as a city. Duluth annexed Lakeside in 1893.

These new neighborhoods rising from the lake east of and including Endion—as well as Hunter’s Park—were particularly attractive to wealthy Duluthians eager to distance their families from Duluth’s increasingly crowded and dirty downtown. Along the river, another financial panic would spur Duluth’s western expansion.

In 1886 the West Duluth Land Company purchased the property surrounding Oneota from Thirtieth Avenue West to Kingsbury Creek and convinced Oneota to join its new Village of West Duluth. The land company aggressively lured metal fabricators to West Duluth, claiming it would become a “new Pittsburgh,” a promise that seemed assured when Oneota’s Merritt family opened the Mesabi Iron Range seventy miles north of Duluth in 1892. That year the Merritts began building their own railroad and ore dock, both heavily financed by John D. Rockefeller. Their Duluth, Missabe & Northern Railway (DM&N) made its first Duluth delivery in July 1893—two months after yet another financial panic destabilized the national economy.

The Panic of 1893 didn’t crush Duluth as had previous panics, as America still needed what the city provided: grain and flour for bread, lumber for homes, and coal for heat and power. But West Duluth’s steel industry struggled, and most metal manufacturers failed. Worse, Rockefeller exploited his agreement with the Merritts, overvaluing his own contribution and calling in loans made to the Merritts when he knew they did not have the cash to pay him back. He took complete control of the Merritts’ mining and railroad assets, an act many have described as larceny. By the year’s end the village turned to Duluth, hoping to survive by annexation. In January 1894, West Duluth—including today’s neighborhoods of Oneota, Irving, Fairmount, Denfeld, and Cody—joined the city.

Cody was named for Cody Street, itself named for William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody whose sister Helen married labor journalist Hugh Wetmore and moved to Duluth in 1893. Two years later year she opened the Cody Sanatorium, advertised as a “place for delicate women and children to rest and recuperate.” After it burned in 1896, Buffalo Bill financed a home on the sanatorium site for the Wetmores, who named it Codyville. (He also paid for their Duluth Press Building at 1915 West Superior Street, which housed Wetmore’s newspaper; both still stand.) Codyville actually sits above the Cody neighborhood in Bayview Heights, which Duluth acquired in 1895. Bayview shares a border with Proctor, originally named Proctorknott for the Kentucky senator who ridiculed Duluth in 1871. Proctor contained the DM&N’s rail yard, and Bayview housed many of its employees.

The 1895 annexation also acquired the property between Grassy Point and Fond du Lac along the St. Louis River in the shadow of Spirit Mountain. Immediately west of West Duluth sat Ironton, so-named to attract a steel plant. Next came Spirit Lake Park, adjacent to Spirit Lake. Beyond that, New Duluth stretched to Fond du Lac’s border at Sargent Creek. In 1890 Atlas Iron & Brass Works relocated from central Wisconsin to New Duluth and built houses, churches, hotels, and stores for its employees. But the company failed following the panic, dooming New Duluth; meanwhile, Ironton and Spirit Lake Park had remained relatively undeveloped.

Duluth was also determined to take Fond du Lac in the same annexation. Besides its brownstone quarries, the village had become a tourist destination, with excursion steamers carrying Duluthians upriver to its shores for weekend outings on the picnic grounds of Chambers Grove. By 1895 Nekuk Island had become Peterson Island, home to a resort hotel. Fond du Lac’s leaders hesitated, worried their community wouldn’t receive proper aldermanic representation. It reluctantly joined Duluth on January 1, 1895.