The Expansion of I-35 Through Duluth

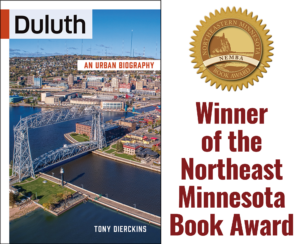

The 1899 DM&IR Endion Passenger Station was moved from 15th Avenue East and South Street to Canal Park during the I-35 Expansion. (Image: Duluth Public Library)

First planned in the late 1950s, the expansion of Interstate 35 through Duluth took thirty years. Plans changed many times, and while the effort advanced the city’s urban renewal, portions of it were highly controversial, as Duluth lost not just its outdated industrial complexes but entire neighborhoods as well.

Starting in the 1960s, the city and the state highway department purchased, condemned, and demolished buildings to make way for the highway’s first extension, from Thomson Hill to downtown. Its path included nearly the entire lower portion of Oneota, former home to National Iron Works (later Davidson Printing), Duluth Brass Works, and Universal Match (later Chun King). Oneota was also home to about 1,600 people whose houses stood among the factories. Bulldozers and wrecking balls destroyed every structure between Michigan and Oneota Streets.

The creation of Oneota Industrial Park took more than two dozen additional homes in the late 1970s. While unhappy residents worked to derail the project, other residents—pleased to get fair-market value for their unsellable homes—countered their effort, which failed. Still more were taken in 1980 and 1981 for the construction of the Richard I. Bong Memorial Bridge, which also created what was called the Oneota Isolation Pocket, a two-block area containing twenty- ve houses bounded by the bridge, Superior Street, railroad tracks, and industrial yards. The last of these homes came down in 1984.

East of the ore docks, highway expansion and urban renewal doomed the Helm Addition, also known as Slabtown, between Thirtieth and Twenty-Fifth Avenues West from Superior Street to the bay. Down went more houses, corner grocers, and factories, including most of Duluth Brewing & Malting, forcing the brewery to close. By the time I-35 pushed through the area in the 1960s, the project had destroyed 232 houses, displacing the families that called them home.

The highway expansion also dramatically altered the waterfront district between Eighth Avenue West and the Minnesota Slip. The grocery- and hardware-distribution warehouses east of the slip eventually all came down, as did facilities for the Northern Pacific and Omaha Road railways.

The most controversial portion of the project eventually pushed the highway through downtown to its northern termination at Twenty-Sixth Avenue East. Original plans called for the highway to run along the lake- shore in front of parks and homes from downtown to the Lester River, essentially cutting o public access to Lake Superior. Public outcry and citizen lawsuits led to dramatic changes to the plans. A series of four tunnels prevented the partial destruction of Leif Erikson Park and the demolition of historic Superior Street buildings between Fifth and Seventh Avenues East including the Pickwick restaurant, Fitger’s Brewery complex, and the Hartley Building.

Still, many more buildings were lost, including all those along the lower side of Michigan Street from First Avenue West to Fourth Avenue East. Demolition crews destroyed every building between Fourth and Fifth Avenues East along lower Superior Street and from Fifth to Eighth Avenues East on the street’s upper side. They included the 1870 Branch’s Hall, the city’s first brick building, along with facilities that made up Duluth’s so-called Automobile Row—car dealerships, repair shops, auto parts stores, and filling stations.

Thirteen houses and several buildings along the lower side of South Street between Fourteenth and Twenty-Sixth Avenues East also met the wrecking ball. Along London Road, the project demolished the Flamette Motel, a gas station, a liquor store, and the Lemon Drop restaurant. Officials spared the Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range Railway’s Endion Pas senger Depot, built in 1899 at the foot of Fifteenth Avenue East, by moving it to the Canal Park business district.

The expansion forced Duluth to get creative with undevelopable property adjacent to the highway. Space beneath overpasses in West Duluth and the West End became Keene Creek and Midtowne Parks. East of Lake Avenue the city created Lake Place (recently renamed Gichi-ode’ Akiing) on top of a highway tunnel, and three other downtown parks—Gateway Plaza, Jay Cooke Plaza, and Rail Park—were all by-products of the project. The I-35 expansion also inspired the Duluth Lakewalk and provided a major makeover of Leif Erikson Park’s Rose Garden.