From Promise to Panic (1870–1877)

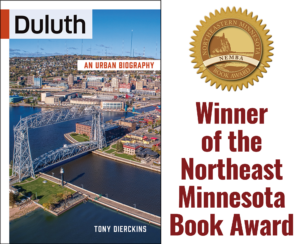

The left half of Gilbert Munger’s 1871 oil painting of Duluth, showing Elevator A and the Breakwater (left) as well as a steam-powered sidewheeler tied up at Citizen’s Dock. (Image: Duluth Public Library)

Duluth continued to boom during its first three years as a city. More immigrants poured in to build the railroads. Loggers clear-cut the city’s hillside, defining its streets and providing timber that Culver’s and Munger’s sawmills cut into the lumber that became the city’s first houses, churches, docks, and warehouses. Duluth’s Minnesota neighbors joined in the prosperity: the Oneota sawmill also cut boards for buildings, and its nearby brickyard made the material to face them; three quarries in Fond du Lac stayed busy providing brownstone for foundations and trim. In the summer of 1870 LS&M director William Branch and friends financed Branch’s Hall, Duluth’s first brick building, at 416 East Superior Street. The LS&M was completed in August, after which daily train service shifted the city into another gear. Grain from St. Paul began arriving by the trainload, loaded onto vessels at the LS&M docks, and shipped east to mills along the Great Lakes.

Not that everything ran smoothly. In May of 1870 newly appointed police chief Robert Bruce skipped town owing creditors about $3000—worth over $60,000 today—and was never heard from again. The city’s wooden fire hall burned to the ground in October 1871, just months after the volunteer fire department obtained its first engine, which was destroyed in the conflagration.

Meanwhile, travelers flocked to the comfort of the railroad, all but abandoning the Military Road, and commerce bypassed Superior. Since Duluth’s business district sat seven miles from the Superior Entry, the city built an outer harbor. Mayor Culver financed the construction of Citizen’s Dock, a municipal wharf for commercial and passenger vessels extending into the lake from Morse Street. East of the railroad’s facilities along the lake between Third and Fourth Avenues East, Munger and Markell began building grain elevator A, financed by the LS&M.

The LS&M also financed arguably the most important piece of infrastructure ever constructed in Duluth: Its ship canal through Minnesota Point. The dredging tug Ishpeming began digging in early September, paused over the winter, and was resumed in April and its first cut complete in early May of 1871 (read more about the digging of the canal here). That summer the Northern Pacific Railroad began constructing docks, wharves, and a rail line on the swampy land between Minnesota Point and Rice’s Point above the canal site, creating a massive commercial district. Once the canal and NP facilities were complete, the only thing in the way of Duluth’s future success was its neighbor across the bay—and Superior’s citizens were not happy. The digging of the canal set off a six-year legal battle between Duluth and both Superior and the State of Wisconsin.

Superior was then smarting from yet another blow to its future. Three months before the canal was complete, Kentucky representative J. Proctor Knott delivered a scathing speech to Congress designed to scuttle a massive land grant proposed for a railroad between Hudson, Wisconsin, on the St. Croix River to Superior and Bayfield on Lake Superior’s South Shore. But he confused Superior with the Zenith City, titling his speech “The Untold Delights of Duluth” and lacing it with what were then considered humorous barbs. Knott’s colleagues interrupted him with their laughter sixty-two times with “roars of laughter.” But while the speech made Duluth a laughing stock, it ended Superior’s chance for its own railroad.

Despite the legal battle, by the summer of 1873 the canal bustled with shipping traffic while Superiorites eagerly awaited their railroad. Vespasian Smith, an Ohio physician, became mayor of Duluth—Luce had resigned in February, returning to Ohio to run the family farm. Dr. Smith, despite running unopposed, was elected with one vote cast against him—and he claimed it was his own. The new mayor oversaw a population of roughly five thousand. And then Jay Cooke ran out of money.

Following the Civil War, Jay Cooke and others had over-invested in railroads. In 1873 the Philadelphia financier was expecting a federal loan of $300 million—about $6.5 billion today—but rumors that his bank had no credit torpedoed the transaction, forcing him into bankruptcy on September 18. Other banks soon followed suit, setting off the Panic of 1873, the beginning of an economic malaise that lasted six years. Within two years 110 railroads failed and 18,000 US businesses closed.

The depression even affected European economies, but few communities were hit harder than Duluth. Financed either directly or indirectly by Cooke’s enterprises, nearly half of the city’s businesses disappeared within two months. As in 1857, people fled in flocks. Van Brunt reports that one resident remembered Duluth’s population dropping to “1300 souls” by the middle of 1874. More reliable sources estimate it at 2500—half the pre-panic number. Even Dr. Foster abandoned his Zenith City, leaving the Minnesotian to his sons, who later sold it to his rival, Mitchell.

By then Duluth and Superior were again sparring over the canal. After Cooke’s bankruptcy the NP had failed and was undergoing reorganization, leaving no money to build Superior’s promised infrastructure. The Wisconsin town felt it was within its rights to seek reparation and had clear evidence that the lack of a railroad had cost it commerce: in 1874, while 290 commercial ships called on the port of Duluth—moving tons of grain, coal, and other goods—not a single vessel passed through the Superior Entry. Wisconsin began filing lawsuits that December.

The canal dispute was just one of Duluth’s problems. The LS&M had also fallen into receivership, and plans for its reorganization had yet to materialize. And while the exodus had slowed, the city’s population continued to drop. Those who remained held out hope that once the Red River Valley along the Minnesota-Dakota Territory border blossomed with wheat and other grains, Duluth—with its railroads, grain terminals, ship canal, and both outer and inner harbors—had the infrastructure in place to turn itself into the major shipping center its forefathers had foreseen. If it could just hold on until then.

Dr. Vespasian Smith,“a staunch, sterling old character that builded well with his great common sense,” was reelected in 1874, this time by three votes (“I made two enemies,” he reportedly said). While Smith was credited for his ability to keep Duluthians “thinking sensibly,” he did not run for re-election in 1875. That year Peter Dean, a dry-goods merchant from New York, ran on an idea that many of the city’s founders did not find sensible: repudiation, essentially disputing the validity of a contract and refusing to honor its terms—a tactic used to reconstruct southern states following the Civil War.

Dean suggested Duluth simply default on its debt, clearing its books while simultaneously wiping its creditors’ investments—but many of those bond owners were the city’s civic and business leaders. Described as a “bluff and gruff and hearty” man who loved Duluth, Dean won the election but couldn’t sell his idea to the city council. Van Brunt called Dean’s time in office “dark days indeed; business was at a standstill; no one had money with which to pay taxes; city debts were unpaid; interest on the bonded indebtedness was permitted to run on.” The 1875 census found 2415 people struggling to make a living in the Zenith City, with another 110 in Oneota and 125 more in Fond du Lac doing little better.

When tailor “Uncle John” Drew replaced Dean as mayor in 1876, he and others recognized that while repudiation was not the answer to Duluth’s economic problems, it would take an equally bold move to pull the city out of the financial muck. Meanwhile, the city owed a lot of money to its bondholders—about $500,000 not including interest by one estimate, more than $12 million today. Drew and the city’s aldermen, treasurer, and comptroller decided that to rebuild Duluth’s financial house, they first had to burn most of it down.