Duluth’s Park System, 1856 – 1956

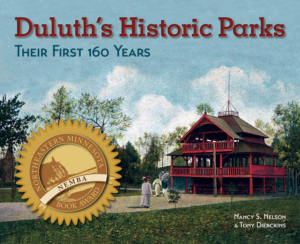

Lithographic postcard, ca. 1904, of a coaching or “Tallyho” party touring Rogers Boulevard, today’s Skyline Parkway. (Image: Zenith City Press)

The Roots of Duluth’s Modern Park System

Duluth’s promoters believed the city would one day rival Chicago, and they knew such a city had to contain this new type of urban park. William K. Rogers is credited with proposing a park system for Duluth that included a scenic hillside parkway connected by stream corridor parks to a boulevard along the shore of Lake Superior. Rogers presented his ideas to the Duluth Common Council (similar to today’s city council), which officially adopted his plan in February 1888.

It’s relatively easy to set aside parks by platting before the land is sold to private individuals. But to carry out Rogers’s plan for a connected park system meant the city had to purchase many acres of land already in the hands of private landowners. Led by Rogers, Duluth’s leaders petitioned the state legislature to create a citizen commission with the authority to develop the park system. In March 1889, the State Legislature approved “An Act Providing for a System of Public Grounds for the City of Duluth.” This legislation created Duluth’s first Board of Park Commissioners and gave it broad powers to acquire land, make improvements, and adopt regulations to guide the use of parks. Along with the power to condemn and take land, the board could issue bonds to borrow money for purchasing land. It could also levy special assessments on nearby property that benefited from the development of the parks and parkways.

Made up of William K. Rogers (president), John H. Upham (vice president), Frederick W. Paine (secretary-treasurer), Roger S. Munger, and Mayor J. B. Sutphin (as an ex officio member) the park board members met for the first time on May 22, 1889. They prepared a list of the land they intended to acquire, namely a narrow strip along the lakeshore and a corridor of land for a parkway (referred to then as Terrace Parkway, later Rogers Boulevard, and today as Skyline Parkway) that would extend from Chester Creek across the hillside to Miller Creek.

With the enthusiastic Rogers at the helm, the park board went to work immediately on the hillside road, hiring appraisers to determine the value of the land and seeking bids from contractors. They secured a loan from the city for $5,000 at 8 percent interest, and construction began on Tenth Street at Lake Avenue.

By early August 1889, President Rogers reported that the first section of the parkway was being used and appreciated by citizens of Duluth and visitors to the city. He also reported that considerable rock blasting was required from Seventeenth Avenue West to Eighteenth Avenue West, significantly increasing the cost of construction. The board members authorized the additional expenditure even though they did not yet have the money to cover it.

Over the next few months, money flowed out as the park board purchased land, rented office space, and hired a clerk to assist the appraisers and engineers. Expenditures on the parkway added up to $5,810.54 by the end of 1889. The following year the board members continued to purchase land, and they estimated that expenses for 1891 would be $24,000.

The park board’s attempts to issue bonds for the needed money met with numerous roadblocks. In August 1889, they asked Mayor Sutphin to hold a special election on the question of issuing park bonds. The mayor designated September 23, 1889, for the special election, but the common council neglected to appoint election judges. When the board repeated the request for a special election, the mayor set October 23, 1889, as the new date; once again the council failed to appoint election judges far enough in advance. The special election finally took place on October 29, 1889, and Duluth’s citizens overwhelmingly gave their approval. However, problems with the New York firm hired to handle the bonds resulted in a cancellation of the entire deal, and no money was raised.

The bills continued to mount. On April 23, 1891, the Duluth Daily Tribune reported that:

Orders having been issued from time to time to workmen who have had to wait unduly for their pay, and other parties who contracted to sell property to the board have not received their money as promised. There have been some unfortunate results from attempts to float the park bonds that, in the opinion of city authorities, have tended to hurt the credit of the city.… The park commission should be reorganized upon a firm basis with men of recognized financial ability at its head.

City officials realized changes had to be made. They requested revisions to the legislation, and state legislators approved these revisions on April 6, 1891. The new act narrowed the park board’s powers. The board could no longer have its own treasurer; all money had to remain in the hands of the city treasurer. The board also had to prepare a map and a statement showing how much money it had or could raise to pay for land it intended to buy, and the council had to approve each purchase.

Mayor M. J. Davis promptly appointed three new park commissioners: Luther Mendenhall, Bernard Silberstein, and Henry Clay Helm, all successful businessmen who were widely respected in the community. William K. Rogers remained a member of the board; when straws were drawn, he received a one-year term.

Mendenhall, president of what would become the First National Bank of Duluth, was elected president. An April 23 Daily Tribune article assured the public, “With Mr. Mendenhall as president the commission ought to have first class standing in financial circles.”