The Tunnels of Subterranean Duluth

Unbuilt: The Minnesota Point Tunnel & Twin Ports Subways

Imagine a Duluth where instead of an Aerial Lift Bridge, in its place is a four-lane brick tunnel which connects Minnesota Point to Canal Park. Instead of the lazy residential strip with sandy beaches and park, the tunnel under the canal connected the railyards of Rice’s Point to twenty linear miles of dock space that connected with a long string of warehouses, manufacturing concerns, and shipping terminals. This was a dream for Duluth in the days before we bridged the canal.

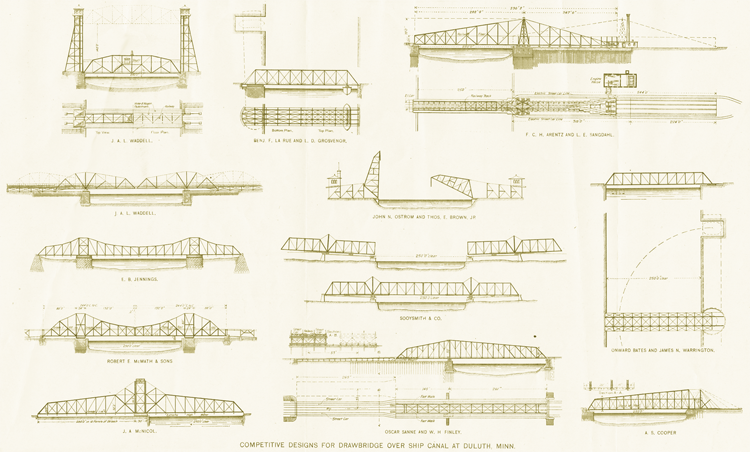

Entries to Duluth’s 1891 contest for a bridge over the Duluth Ship Canal. (Image: Zenith City Press)

The Minnesota Point Tunnel

After the city had dredged a canal to make an island of Minnesota Point, there became the immediate problem of bringing goods and people to the other side. While ferryboats immediately filled this need, citizens of the Zenith City knew there had to be a long term solution. Two competing methodologies were put forth: Duluth could bridge the gap, or tunnel under it. And, be it bridge or tunnel, the pathway across the canal would include a pedestrian lane, a lane for horses-and-wagon teams, and two lines of heavy gauge rail that would facilitate the industrialization of Minnesota Point, making Duluth the largest port on the planet—inland or otherwise. They expected the population of Park Point to grow to 10,000.

An 1890 idea for a swing-arm bridge failed to meet standards of the U.S. Corps of Engineers: the federal government owns the canal, and it would not allow such a large mechanical bridge to cross the canal because there was too great a chance for failure—and that would block shipping traffic, which is the sole purpose of the canal. So, Duluth asked William Sooey Smith of Chicago to design a tunnel that would drop below the surface along St. Croix Avenue—today’s Canal Park Drive—and reemerge several blocks south of the canal a few blocks closer to Park Point.

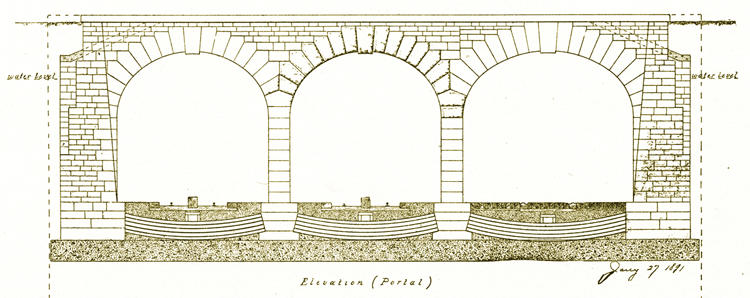

Smith’s 1891 tunnel plan to traverse the ship canal. (Image: Zenith City Press)

Smith’s plan featured a four lane-tunnel with the features described above. He also offered an alternate three-lane plan with just one rail line. Smith explained that all the work for the tunnel could be done while Lake Superior was frozen, and construction would therefore have no effect on shipping traffic. Duluth never even submitted Smith’s plan to the Corps of Engineers as the estimated price tag of $1.4 million (over $30 million today) put an early end to all discussion of the proposal. A contest in 1891 failed to provide the city with a design the government would approve. While it did not win the contest, one submission posited a bridge with a raisable horizontal span. A “lift bridge” if you will. This brand-new idea by John Alexander Lowell Waddell was large enough to carry to lines of heavy gauge rail and, since it would have been steam powered at the time, the government thought it was too likely to fail and block shipping traffic. Instead, Waddel’s bridge was built in Chicago, where it still famously stands.

It took until 1901 before Duluth came up with an idea the Corps of Engineers could live with: a transfer bridge. Since it took one “load” at a time, the transfer bridge could not be used to carry trains, and the idea of industrializing Minnesota Point was essentially abandoned by everyone except the editorial department of the Duluth News Tribune.

Duluth’s Aerial Transfer Bridge photographed on its first day of operation in 1905. (Image: Duluth Public Library)

During its 25 years of service, the transfer bridge became more obsolete as automobiles became more prevalent, and by 1917 it was already considered obsolete by some. That year papers again buzzed with excitement about subterranean possibilities. The August 3, 1917, edition of the News Tribune stated: “It is known that until the tunnel is built Park Point cannot be what it logically must be—a railroad terminal and location for docks, warehouses and industries.”

Those in favor of the tunnel pointed out that the ferry bridge was aging, expensive to operate and maintain, and it could not keep up with demand. Even in 1891, when it became clear a bridge would cross the canal and not a tunnel, the News Tribune had predicted that a tunnel would eventually replace whatever bridge was erected atop the canal when “the city felt it was able to tunnel the canal.”

March 22, 1893 Board Gets Ready (Image: Duluth News Tribune)

That time never came. By the mid-1920s, it was clear that soon there would not be enough hours in the day for the ferry bridge to convey all the traffic that needed to cross the canal. But by then Minnesota Point was not needed to expand the port of Duluth, and Park Point’s population would not reach 10,000 as expected 35 years earlier. Duluth needed a new way to cross the canal, but traffic would never reach the point to justify the enormous cost of a tunnel. Instead, Duluth hired John Harrington’s Kansas City Bridge Company to convert the ferry bridge into a lift bridge. Harrington knew a lot about lift bridges; he was once a protégé of John Alexander Lowell Waddell, who had tried to get Duluth to build one in 1891.

Though a tunnel was never dug under the ship canal, when its concrete piers were installed in the 1890s, a tunnel was constructed as part of the new South Pier breakwater.

The South Pier Tunnel was very small and prone to flooding. Today it is filled in. (Image: Zenith City Press)

The tunnel ran from east of where the Aerial Bridge would be built and lead to the South Pier Light at the end of the canal. This was done to provide passage for lighthouse keepers during storms. Lake Superior’s waters often breached the canal’s piers during heavy storms, and walking the piers could mean being swept into the lake or, even worse, the canal. Inside the tunnel was a set of steel rails, upon which sat a wheeled cart. A cable stretched from one end to the other, thus allowing the lighthouse keeper to pull himself back and forth through the tunnel using the cable. An awkward process, although that is not the reason the cart and rails are gone today; the tunnel was not even water tight. Because the tunnel flooded often, it was eventually abandoned. Now the entrance is filled with concrete.

Superior Street Subway

While it may seem outrageous today, in 1914 city leaders proposed a full-scale subway system for downtown Duluth below Superior Street. At a time when the city’s population was booming and its citizens imagined themselves as founders of a western Chicago or New York City, it may have seemed more reasonable. Such a system, it was argued, would relieve the impending extreme traffic congestion through the city’s main thoroughfare. As a bonus, the subway could be built without impeding street traffic, thanks to the strength of Duluth’s granite-basalt underbelly.

Of course, this type of stone is also very difficult to remove and shape, but the idea’s author stated that he, “…takes issue with probably opinions of engineers that the work would be impractical, unwarranted and excessively expensive.” On an understandably dismissive note, the Duluth News Tribune reported that, “The Mayor has filed [the subway suggestion] for future reference.”

The Duluth-Superior Express Tunnel

When the tunnelers of Duluth were denied passage under the canal and below downtown Superior Street, some looked beneath the waters between Superior and Duluth of Rice’s Point and Connor’s Point. The Interstate Bridge was the principal artery for both cities, carrying wagons, pedestrians, trolleys, and eventually automobiles. But all traffic stopped when the swing-arm draw bridge swiveled to allow ore boats and other vessels to pass into the harbor. In 1906, the steamer Troy collided with the bridge, shutting down traffic for months, putting ferries to work transferring people and goods between the two cities.

A lithographic postcard showing the damaged Interstate Bridge after it was rammed by the steamer Troy in 1906. (Image: Zenith City Press)

In a time when rail men and vessel men had little to agree on, it was clear this crossing was a mutual annoyance, and an increasingly expensive one. At a 1916 Commercial Club meeting, Duluth, Missabe & Northern Railroad’s William Albert McGonagle argued that a tunnel would serve the interests of all, although he admitted that the cost of the project would be immense.

McGonagle’s plan was to dredge a trench between Rice’s and Connor’s points at the bottom of the bay and sink three sections of steel pipe into it: one for trolley cars, automobiles, and pedestrians and two for trains. Then, the pipe would be sealed, covered, and bored to from both Minnesota and Wisconsin before being pumped dry. When Duluth Mayor William Prince was asked about this plan, he was encouraging:

I am in favor of a tunnel across the bay at Rice’s Point, and also one at the aerial bridge… it is not impossible that an arrangement could be made by which the cities of Duluth and Superior and the railroads could divide the expense among them, and the Federal government might be induced to contribute part of it.

Connor & Rice’s Points (Image: Library of Congress)

It seems that the desire to tunnel between the states died when the third proposed tunnel below the ship canal was rejected, though, as the matter was seemingly never revisited. The Arrowhead Bridge was built in 1925, connecting Superior to West Duluth and relieving some congestion the Interstate Bridge. The Interstate Bridge was replaced by the Blatnik Bridge in 1961 and the Bong Bridge took over the duties of the Arrowhead Bridge in 1985.

The Arrowhead Bridge. (Image: Zenith City Press)

Today, Duluth’s most prominent subterranean passageways are the series of tunnels along I-35 through Duluth, the construction of which, it is said, uncovered a secret tunnel between 8th and 9th Avenues east, leading essentially from the Kitchi Gammi Club to the lake. Some members of the Kitchi Gammi Club swear the tale is true, and the tunnel is a remnant of Prohibition, once used to smuggle in booze for Duluth’s elite. Recently owners of Expert Tire at 7th Avenue East and First Street believe they too found a bootlegger’s tunnel while accessing damaged caused to the building during the 2012 flood.