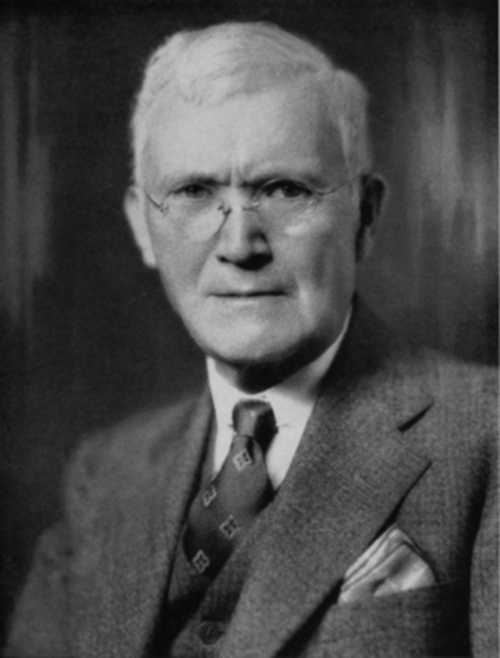

Thomas Shastid

Duluth’s Thomas Shastid in 1940. (Image: Zenith City Press)

In 1926, the two-volume novel The Duke of Duluth hit the streets of the Zenith City, penned by Dr. Thomas Shastid, a prolific writer and eye doctor once called “America’s forgotten historian of ophthalmology.” Shastid theorized that Abraham Lincoln was colorblind and predicted that human evolution would eventually eliminate the left eye and move the right to the center of the face. His Duluth novel was not well received.

Shastid grew up in Pittsfield, Illinois, where his grandfather was friends with Lincoln long before Abe entered politics. The future ophthalmologist self-published his first work in 1880 at the tender age of 13, a collection of poems titled Newspaper Ballads. A year later he released a second collection titled simply Poems.

In the 1890s, Shastid attended medical school at Harvard and returned to his hometown to practice medicine, later moving north to Galesburg. Both towns were part of Illinois’ Pike County. During this period he wrote two memoirs, 1898’s A Country Doctor and Practising in Pike in 1908, and also began a side career as a legal and science writer. Between 1906 and 1936 the years he wrote three books on medical malpractice, three on ophthalmology, and was a major contributor to the eight-volume American Encyclopedia of Ophthalmology, During the latter half of the 1920s he turned his thoughts to ending war, giving speeches and turning those talks into five small books.

In 1937 he published How to Stop War-Time Profiteering (1937) and an autobiography titled Tramping to Failure. The well-travelled Dr. Shastid liked to consider himself a hobo of sorts. In the memoir, he refers to himself as “The Tramp” and called his home, which he purchased from August Fitger, “Tramp’s Rest.” Apparently, the Tramp’s life was successful enough to warrant a second autobiography, published in 1944 under the title My Second Life.

Sometime after 1908, Shastid made his way to the Head of the Lakes, at first setting up shop in Superior and eventually crossing the bay to Duluth. It was here, between 1923 and 1926, that Shastid published three novels. The first, 1923’s Simon of Cyrene (1923), is an allegorical tale of the life of Simon of Cyrene. He followed that a year later with the morality tale Who Shall Command Thy Heart? Then, in 1926, Shastid released a two-volume novel titled The Duke of Duluth. It was to be the first in a quartet of novels titled “The Nobility of the Midwest” that would include The Earl of Superior, The Marquis of Minneapolis, and The Sieur de St. Paul. The Duke was the first and last published; it is unknown whether he even began any of the other books.

The Duke in question is archetypal everyman John Smith, who travels from Safe Center Iowa to Duluth to receive a surprise inheritance from a deceased uncle. At the lawyer’s office, he meets his shiftless cousin Claude Tyrone, nearly identical in appearance to John but his mirror opposite when it comes to morals. Claude only likes to obtain things “in the easiest way.” Our hero also meets Jean, the lawyer’s secretary and a direct descendant of Daniel Greysolon Sieur du Lhut and an Indian maiden. (du Lhut was famously known as a love-lorn bachelor who never wed and had no children; Shastid’s knowledge of Duluth history is full of misconceptions—he also credits Proctor Knott as first calling Duluth the “Zenith City of Unsalted Seas.”) Jean is a big fan of Duluth, which she refers to as “Mount Service.” She lives on the bluff above the Incline Railway with her mother in a house she calls “Glory Cottage.” To Jean, the clouds over the lake are the great Water Carriers, which bring fresh Lake Superior water to the fields of the western plains, growing the grain that flows back to Duluth and out over the lake to the rest of the world. (Shastid apparently did not notice that the prevailing winds in Duluth come from the west.)

For all of his love for Duluth, and Jean, John quickly leaves the Zenith City. He uses his newfound wealth to enroll in the same Illinois college that Claude attends. There, after an awkward arrival, Claude dubs John the “Duke of Duluth” in jest. But the joke isn’t revealed until nearly the end of the book, as John later explains: “It is a custom in Minneapolis and St. Paul…to rechristen a man who…esteems his own abilities and situation in life pretty highly, ‘The Duke of Duluth.’”

Shastid’s idea of what defined a “Duke of Duluth” may have some reflection of the truth in it. Two of the books’ reviewer use a similar explanation of the title. One stated, “whenever anyone is supposed to esteem somewhat too highly his own appearance, ability, desserts or station in life, he is termed by courtesy ‘The Duke of Duluth.’” The second wrote, “Whenever any person is included to esteem his personal appearance, ability or station in life too highly, he is termed ‘The Duke of Duluth.’” The same reviewer later states that “this expression, ‘The Duke of Duluth,’ is given an entirely different meaning from that which it normally bears.” (Emphasis added.) Though no use of the term could be found elsewhere, the phrase “Duke of Duluth” may have been used derogatorily at this time, and was perhaps inspired by the 1905 musical of the same name, in which a boastful hobo is mistaken as “the Duke of Duluth.”