Duluth’s 1920 Lynchings

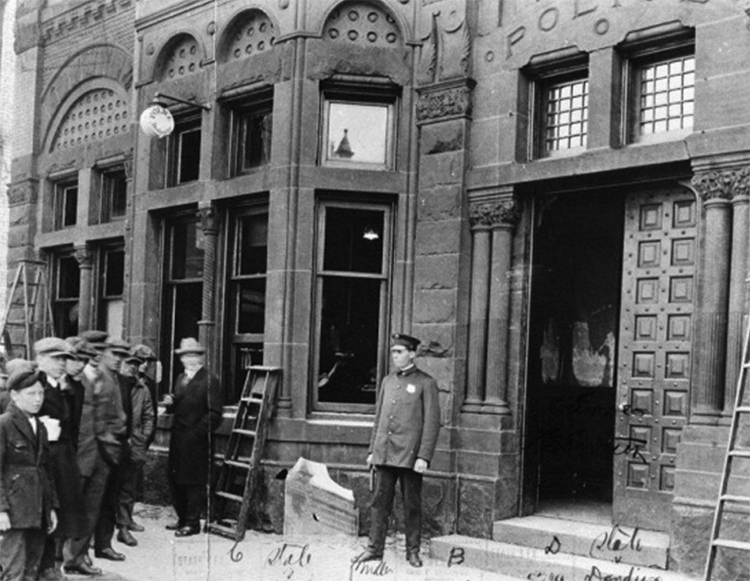

A lone Duluth police officer stands outside the headquarters and jail on June 16, 1920—the day after the most notorious day in the history of the Zenith City. (Image: Duluth Public Library)

The Questions

There are a thousand whys, only some of which can be answered through the filter of years and the clarity of distance. Why were Sullivan and Tusken so readily believed on such flimsy evidence? Why was such an incredibly large crowd (one in ten of Duluth residents) eager to join in such a horrifying melee? Why did the Commissioner not call on the National Guard, which was gathering just a few blocks away for weekend duty? Why did he order the 11 police officers in the jail to put their guns away? Why were the perpetrators left almost wholly unpunished? Why did it happen here?

But there is one question that burns hotter than most—a question that can never be answered. Was Tusken truly the victim of a crime? Marshall Johnson, a sociology professor at UWS reports that one of his students contacted a relative of Tusken’s some time after Tusken’s death. Reportedly, the relative confirmed that Tusken was not raped. Still, no one was able to settle the question before Tusken’s death. If her accusation was false, it is likely that Tusken felt strong pressure to keep quiet.

The questions overwhelm. It is not hard to see why the almost immediate response of many Duluthians was to try to forget. The Duluth News-Tribune on June 17, 1920, printed an editorial entitled “Duluth’s Disgrace.” The editorial stated, “Duluth has suffered a disgrace, a horrible blot upon its name that it can never outlive.”

On June 21, a man identified only as “Jack” wrote in a letter to the editor, “Last week’s happening is indeed unfortunate–it cannot be undone, therefore it is better the quicker it is forgotten.”

The Aftermath

Indeed, during the years since the lynching, the effort to forget has been strong. A St. Louis County Historical Society employee in the 1940s reportedly threw out the file on the incident, deeming it too unseemly for study by Normal School students. All but a silent few forgot the location of the victims’ unmarked graves. Minnesota History courses required teachers in training did not mention the incident. Postcards made to celebrate the incident quickly sold out immediately afterward but were eventually hidden away in attics. Many of the men and women present that night did not speak of it again. One of the police officers who defended the jail, when questioned about it in the 1970s, claimed to have no memory of a night that must have been the most significant experience of his career.

At the Duluth Public Library, there is only one well-worn box in the Duluth News-Tribune microfilm archives—the rest look nearly untouched. The box, repaired with yellowing tape, contains the newspapers from June 15, 1920, and the weeks afterward. For years, people who wanted to know anything about the horror of that night found this box the only commonly available source of information.

However, in the minds and histories of some Duluthians, the story did not disappear. The day after the lynching, “idle Negroes” were banished from Superior, forced to walk across the bridge to Duluth, prompting panicked calls to police by fearful whites. For months, some black residents received terrorizing phone threats. People banded together for safety, putting the children to sleep upstairs while the adults stayed awake in darkened front parlors watching for trouble. Housing became even more difficult to attain, and many jobs were suddenly unavailable to people of color. In the few years after the lynching, half of Duluth’s African-American population moved away. Those who stayed kept the memory of the victims alive by honoring the Crawford Mortuary with the business of mourning their dead. Crawford was the funeral home that accepted the bodies of the lynching victims after another funeral home refused.

Outside Duluth, at least two black men who later made impacts on national politics were deeply affected by the lynching here. Roy Wilkins (long-time president of the NAACP) devotes three pages of his autobiography to his reaction to the incident. Reportedly, the event spurred him to become a civil rights activist. Elisha Scott, the first lawyer to sign on to the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case, was the lawyer hired by Elmer Jackson’s father when he came north seeking reparations for his son’s murder.

The Awakening

Finally, someone stepped forward to break the silence. In the 1970s, Michael Fedo, a Duluth native, prepared to write a novel set in post-WWI America. He planned to include a lynching and remembered hearing, when he was about 10 years old, about a lynching that had occurred here in Duluth. He assumed that a book had already been written about it. “When I learned it wasn’t out there, I decided to write it myself.” And write it he did, putting together an analysis of the times, the mob and the details in such a way to make them readable and easily understood. His efforts, however, were not terribly well received. The publishing arm of the Minnesota Historical Society showed no interest. Twice, small presses published his book under the titles They Was Just Niggers (a declaration made by one of the perpetrators) and Trial by Mob. But then, in 1999, the Minnesota Historical Society changed its position. Now the book is, for the first time, widely available under the title, The Lynchings in Duluth. Within its pages, Duluthians can learn the truth about the most horrifying event in their grandparents’ and great-grand-parents’ lives, perpetrated on the soil of their own hometown.

In the early 1990s, others became publicly interested in addressing some of the story’s missing pieces. First, Henry Banks, then in charge of planning the Martin Luther King Day celebrations in Duluth (now the owner of the Diversity Store), sought some recognition of the site of the lynching itself. He feels that part of the reason the lynching has not been lived down is because it is being hidden away. “Young people needed to know so that [history] didn’t repeat itself.” The NAACP-Duluth subsequently joined in an effort to raise awareness and place a wreath at the site. This effort spurred further action and research by former president of the local NAACP, Bob Baldwin, in order to permanently mark the site with a memorial. Unfortunately, this effort faded.

Soon after, a dispute over the placement of the new county jail led to the discovery of the gravesites. In an effort led by Craig Grau, a political science professor at the University of Minnesota Duluth, it was discovered that unmarked graves in Park Hill Cemetery provided a final resting place for McGhie, Jackson and Clayton. Grau and others established a fund, held a ceremony to place gravestones and used the money left over to set up a small scholarship fund at UMD in the victims’ names. Because of his part in this effort, Grau was later invited to witness the ceremonial naming of an overpass in Topeka, Kan., in memory of Elmer Jackson, the only victim whose life history has been discovered with any completeness.

Since then, small memorial ceremonies have periodically popped up, led by various individual—some known and some not. Last year, people placed flowers and candles, as well as a scrawled list of names calling for a permanent memorial, on the corner where the lynching occurred.

Still, gaps remain, mostly in the area of education. The lynching is a difficult subject to address, no doubt, especially given the short shrift allowed local history in the classroom. However, the fact that almost all junior high and high school students make their way through Duluth schools without even hearing of the lynchings is an oversight not unnoticed by the young adults who are forced to seek information on their own. Mike Piasecki, age 22 and a graduate of Central High School (where Catherine Nachbar, the only Duluth teacher known to address the subject formally, now devotes nearly two weeks to the subject) complains, “We didn’t get much diversity stuff or local history. To this day, I don’t really know why or how it happened. I had to go to the library to find out anything at all.” Eric Edwardson, a 25-year-old Denfeld graduate, says that his teacher mentioned it. “We had a maybe fifteen minute discussion. Kids reacted with shock and denial, saying that it ‘couldn’t happen here.’” Vance Hopkins, Academy Director at Kenwood-Edison Charter School, says he learned of the lynchings in seventh grade. “It’s one of Duluth’s well-kept secrets.” He feels it should be required learning in junior high and high school history classes.