Duluth’s Park System, 1856 – 1956

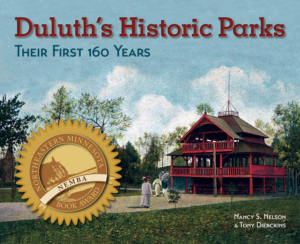

A lithographic postcard showing Tischer Creek within Congdon Park, ca. 1910. (Image: Zenith City Press)

Rock, water, and ice: These forces of nature inspired Duluth’s park system. Eleven thousand years ago a massive layer of glacial ice melted away slowly as the climate warmed. Meltwater collected in the huge basin we now call Lake Superior. Much deeper than today, the shoreline of this lake stood at an elevation of about 1,100 feet—nearly 500 feet above today’s lakeshore. For thousands of years, the waters of the glacial lake washed up against the rock, creating gravel beaches and wave-cut cliffs.

As the ice melted away to the north, exposing more land and new outlets, the water began flowing out to the east through the St. Mary’s River at Sault Ste. Marie. The water level in the lake dropped, leaving the old shoreline sitting high and dry, perched on the hillside above the newly exposed rocky land that would one day become Duluth.

Before 1854, the land on the western side of the St. Louis River was “Indian Territory.” Ojibwe lived in scattered villages, and an all-but-abandoned fur trading post at Fond du Lac still housed a handful of white traders and missionaries.

The 1854 Treaty of La Pointe changed everything. The Ojibwe ceded a large block of land on the western shore of Lake Superior to the United States. They retained the right to hunt, fish, and gather in the ceded territory, but the treaty opened the land to American settlement and speculators wasted no time staking their claims. Between 1856 and 1859, settlers laid out eleven separate townsites in what is now Duluth. In addition to Fond du Lac, the townsites included Oneota, Rice’s Point, Fremont, Duluth, North Duluth, Cowell’s Addition (much of today’s Canal Park business district), Middleton (most of today’s Park Point), Portland, Endion, and Belville. The area encompassed by the townsites of Middleton, Cowell’s Addition, Duluth, North Duluth, and Fremont incorporated together as the town of Duluth in 1857.

The Nineteenth-Century Squares

As the early settlers carved their towns out of the northern wilderness, they also created the city’s first parks or “squares”—one or two city blocks designated as public open space. The squares were set aside from development when the townsites were platted, the process followed when a tract of undeveloped land was divided into smaller parcels connected by streets, alleys, and parks.

Reflecting the role of urban parks in mid-nineteenth-century America, Duluth’s platted squares represented a remnant of the old English system of the commons—unimproved tracts of land in a central area used by the community as a public gathering place. In agricultural England, people also used the commons for grazing their cows and sheep. In America, these urban squares simply provided undeveloped public spaces.

The founders of the Duluth townsite set aside two platted parks: Cascade Square, a four-acre parcel in the heart of downtown, and Central Park (sometimes called Zenith Park), a thirty-acre parcel high on the rocky hillside west of downtown. The developers of several other townsites also set aside platted parks: Lafayette Square and Franklin Square in Middleton (1856), Fond du Lac Square (1856), Portland Square in the town of Portland (1856, now the East Hillside), and five squares in New London (1871, now Lakeside): Washington, Russell, Manchester, Portman, and Grosvenor.

Several of the original townsites joined together in 1870 to form the City of Duluth: Duluth, Portland, Endion, and Rice’s Point. When these towns merged, the new city became responsible for all the platted parks.

But the role of urban parks in America was already changing. Thousands of people were leaving their farms and moving to cities to work in factories. Reformers began to advocate for large public parks with manicured greenspaces that would allow people a chance to escape from long, dreary days of factory work. Frederick Law Olmsted, America’s most famous landscape architect, led the movement to design elaborate urban park systems that included pastoral landscapes with picturesque elements. Olmsted designed his parks to provide residents relief from their noisy, man-made surroundings. Parkways—broad, landscaped boulevards with separate roadways for pedestrians, bicyclists, equestrians, and horse carriages—were an important component of Olmsted’s designs.